chinese whispers, trust entropy, and why blockchains matter

“Chinese Whispers,” also known as “Broken Telephone,” is a popular children’s game that demonstrates how easily information can become distorted when passed through a series of individuals. The game typically involves participants sitting in a circle or a line. The first person thinks of a message and whispers it to the next person, who then passes it on. As the message travels, it often becomes garbled and significantly changes from the original. The final version, announced by the last person, is usually very different from the initial one, and in some cases unrecognizable.

This game illustrates “information entropy,” a concept from mathematics and information theory coined by Claude Shannon in his 1948 paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication.” Information entropy measures the unpredictability in a set of outcomes. In Broken Telephone, each whisper introduces potential errors, increasing the entropy and distorting the original message. This process is akin to a compounding error rate, where noise increases with each transfer, eventually resulting in significant information loss.

But what does information entropy have to do with blockchains? Blockchains deal with trust (or, trustlessness), and if you’ll think about it hard enough, you will recognize a close relationship between how information and trust behave.

Trust and society

Trust is fundamental in society. It’s the confidence in the reliability and integrity of a person or system. We trust our cars, elevators, airplane manufacturers, and food producers. We trust societal rules to protect us from crime.

Trust is essential, but it’s also complex. Trusting someone or a system is a consequence of complex processes each of us is doing when underwriting our trust in another person or system. Humans also frequently use a ‘delegation algorithm’ – if others trust something, we’re more likely to trust it too. The majority of things we trust in our day-to-day is a consequence of trust delegation, we actually verify very little things by ourselves in modern society (if you would try to, you probably won’t have too much spare time to do anything rather verifying all day long).

Trust is everywhere, and society can’t function without it. A mental model that I like for trust, can be thought of as a chain of components, each its own piece of trust. In airplane manufacturing for example, this chain extends across various parties - manufacturers trust vendors to meet quality and safety standards. Airlines trust engineers and designers. Regulatory bodies develop safety standards, and passengers trust these authorities for aircraft safety. Trust also extends to airline staff, from pilots to maintenance crews.

Trust and information

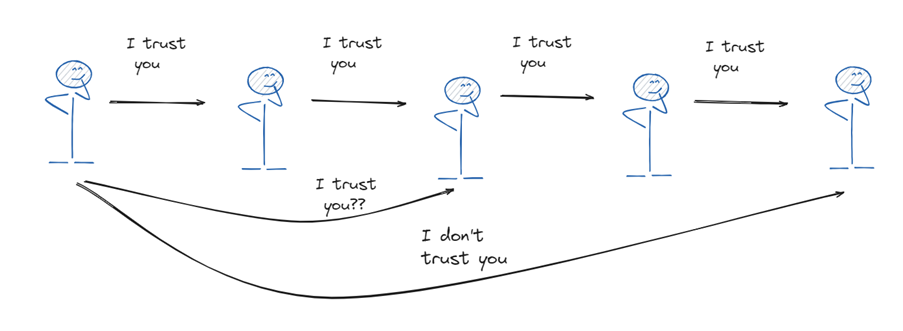

I’ve been playing with the idea that trust is a derivative of information, sharing similar properties for quite some time now. In a trust chain, each node ‘passes’ trust to the next one. However, like in Chinese Whispers, there’s trust erosion with each transfer. A ‘loss factor’ or ‘error rate’ accumulates in the network. Because of that, longer trust chains based on pure human interaction get’s weaker with size. This is an intuitive conclusion if you think of your daily life - It’s easier to verify close interactions than distant ones. For instance, consider the trust you place in a local restaurant versus a distant food manufacturer:

Trusting a local restaurant:

- Personal Experience: You’ve eaten at this restaurant many times and consistently found the food to be delicious and high-quality. You might have met the owners and know who they are.

- Direct Observation: You’ve witnessed the restaurant’s cleanliness and the staff’s meticulous care in food preparation and service.

- Immediate Feedback: The restaurant addresses any concerns or special requests right away, enhancing your trust in their service.

In this scenario, your trust in the restaurant is based on direct, repeated, and personal experiences. It’s straightforward to verify because your interactions with the restaurant and its staff are regular and direct.

Trusting a distant food manufacturer:

- Lack of Personal Experience: You’ve never visited the manufacturing facility, so you have no firsthand experience with the manufacturer’s processes. You have no clue who are the shareholders of the company.

- No Direct Observation: You’re unable to see the product’s creation, the working conditions, or the quality control measures firsthand.

- Delayed or Limited Feedback: Any issues you have with the product can only be addressed through customer service, which might be slow to respond or just not veru personal.

In this case, verifying the food manufacturer is much more challenging. You might rely on reviews, brand reputation, or certifications, but these are indirect ways of establishing trust. The physical and experiential distance introduces more variables and uncertainties, complicating the establishment of trust compared to the local restaurant scenario. I call this concept Trust Entropy.

Trust Entropy increases with the size of collaborating humans

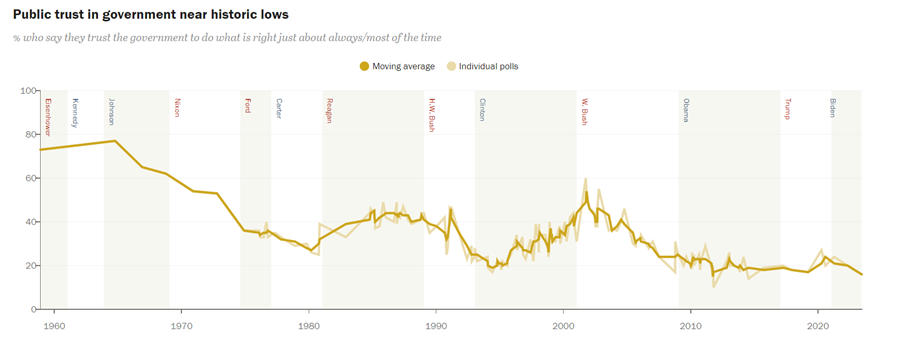

Yuval Noah Harari, in his book “Sapiens,” explains how humans scaled from small groups to nation-states using mechanisms like mass communication and shared culture. We’ve gotten a long way from painting stories on the cave wall – we can use mass communications like radio, TV, and the internet, to spread ideas and information across the world in the speed of light. However, it seems like modern society faces a ‘trust barrier.’ With more information comes more fake news, more conspiracies, and more information warfare. It seems like at some point, trust is eroding. It is no coincidence that public trust in governments is reaching historical lows.

Source1

Beyond a certain point, trust doesn’t scale with current technology. The internet has brought us information efficiency, but it cannot scale trust by itself. Human collaboration is hindered by significant entropy in the trust chain, evident in societal distrust, from vaccine scepticism to conspiracy theories.

‘Don’t trust, verify’

‘Don’t trust, verify’ is a phrase often heard in blockchain contexts. Public blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum allow users to verify the network state (e.g., Bitcoin holdings) independently by running their own nodes, reducing reliance on third parties, and shortening the trust chain.

However, using Bitcoin still involves trust in hardware manufacturers and internet providers, among other things. Blockchain technology requires less trust than traditional systems and shortens the trust chain (but doesn’t eliminate it entirely, which is a common mistake maximalist do). Open-source smart contracts on Ethereum let users verify contracts logic directly. These contracts can replace many trust-dependent societal functions, allowing for shorter trust chains in international settlements, and collaboration across the internet with very low trust barriers.

Why Blockchains

Blockchains provide a verifiable database and logic, creating coordination systems that require far less trust than current mechanisms (I really like Chris Dixon definition: “blockchains are computers that can make commitments”. This is another way of describing trust machines, because commitments = trust enabler). The internet scaled information transfer globally, but the trust component is still lacking. Blockchains matter because they fill this gap. Enhancing trust chains with math and cryptography avoids the errors of human trust transmission, as seen in Chinese Whispers. The idea is that humans don’t have to build these long trust chains, that gets eroded through time. You can use blockchains to reduce the length of these chains or make them more robust. More verifiability means more trust, and more trust means more collaboration.

This is why I believe the blockchain is one of the greatest inventions of this century – it will enable us to collaborate on a whole new scale. The fight against trust entropy is here. We need blockchains to win.

-

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2023/09/19/public-trust-in-government-1958-2023/ ↩